Rowing Across the Atlantic Ocean; My Experience

So, yeah, I’ve just finished Rowing Across the Atlantic Ocean. 2 hours rowing, 2 hours resting, 24 hours a day for 2 months. Trying to sleep in 12 30 minute bursts each day. I hate to sound dramatic, but I have to be honest, it was the worst 2 months of my life. It’s was a brutal mental struggle. The isolation. The claustrophobia. Normally I’m one for suffering in order to reach your goals. I try to make my life all about that vibe. But rowing the Atlantic is different. It seemed to be all the suffering, with none of the joy.

Because, and whisper it quietly, it doesn’t feel like that big of an achievement. The weather and tide do most of the work (the ocean rowing community may hate me for letting the cat out of the bag). You just have to suck up the misery of being stuck on the boat until you reach the other side. So, many times during the expedition I was left in the middle of the ocean wondering “was it all worth it?” The $10k, the 6 months of my life, the chaos, and the mismanagement. The answer? Just about. It was worth it.

Table of contents

- Rowing Across the Atlantic Ocean; My Experience

- First, How Did I End Up Rowing the Atlantic:

- Delays

- Starting the Row and Getting Rescued

- Starting Again, A New World’s First!

- An epiphany

- No Life Raft

- 1000 miles to go

- Antigua BABY!

- The Aftermath of the Row

- Final Thoughts on Rowing the Atlantic?

- What now?

- FAQs about Rowing the Atlantic

- Why Did You Row Across the Atlantic?

- Who Did You Rowing the Atlantic With?

- How Long Did Rowing the Atlantic Take?

- Where Did You Start and Finish?

- How Far Was it?!

- How Much Does it Cost to Row Across the Atlantic?

- But You Can’t Really Swim, Can you!?

- And What About the Boat?

- Would you recommend other people to Row an ocean?

- Would you do it again?

Admitting that the weather and tide do most of the work is a difficult thing because it would be much easier for me to sit back and revel in the adulation that comes from the media, from Instagram, from Facebook, when you finish such a thing. The attention and reverence are alluring and addictive. But during the row, at my darkest spots, I promised myself I’d write an honest account of the experience. So here it is.

Now don’t get me wrong. It’s not entirely without its merit. You have a rare opportunity to truly reflect, for hours, days, weeks, months on end about who you are, your weaknesses, and strengths. What you want from life. That’s a huge plus and it’s an opportunity that is difficult to come by. Back in the real world, away from the huge waves and sleep deprivation, life comes at you fast. Where else on earth do you have the luxury of endless time to think about yourself and your bubble? Only when you row an ocean. That’s the good side.

My experience was quite the ride. Here we go.

First, How Did I End Up Rowing the Atlantic:

If you read my blog post about Ocean Rowing last year when I just found out about it all, you’ll have seen how I managed to end up signing up to row across the Atlantic Ocean last minute. The short version is that I once ran the Marathon Des Sables, a 260km ultra-marathon race in the Sahara Desert. One of the days on that ultra-marathon I partnered with a former marine who told me he had rowed across the Atlantic a few years ago. “WOW,” I thought, “I want to do that“!

He told me to sign up for a Facebook page called the Ocean Rowing Society. What an adventure to tell my Grandkids. I’d make my wife and mum proud. I’d push myself to my physical limit, and sink or swim. It’s everything that I felt my life had been building up to. A true challenge, one where I might meet my match. Unfortunately, as I was to discover, ocean rowing isn’t quite what people think it is.

For a year or 2, I watched all these legends rowing across oceans via Facebook. People seemed consumed by it. And for the people who had completed it, defined by it. Social media profile pictures showing their triumphant pictures upon reaching dry land, even years later.

Finally, during Covid lock-down, I saw a post on the Facebook Page asking for 2 people to complete a team of 4 to row the Atlantic Ocean. This was it. The stars have aligned Johnny boy. It’s your chance to join the alumni. I applied, along with hundreds of others. I made it quite clear I can’t really swim, I’m scared of the Ocean and I have zero experience with boats aside from a ferry between Ireland and England as a kid and those 2 times I hitchhiked on cargo ships – once from Thailand to China on a Chinese cargo ship, and from Oman to Yemen on an Indian cement boat.

Although the advert hadn’t mentioned the financial side of things. It turned out that any applicant had to be ready to pay $20,000 for the honour of taking their seat on the expedition to fund the other 2 members’ participation and the rest of the costs. Eeeek. Anyway, after a couple of rounds of interviews, I was selected, paid my money (reduced to $10k after a last-minute sponsor), and within 6 weeks I flew from Bangkok, Thailand (where I live) back to the UK for a sea-survival course and to meet my new row team.

And that was that, right? Not by a long shot. Then the problems began!

Delays

Delaying my Wedding. Ouch.

Sacrifices. Selfish ones at that. You know, being a Type A personality is often lauded. Single-minded. Driven. Motivated. Sure, sounds great, right? Not always. The downside to all this is a selfishness that carries us Type As through life, and I was guilty of that right from the outset. I was due to get married in February 2021, but the row was due to start in late January. What to do?

After already postponing my first wedding ceremony back in November 2020 due to COVID, it was probably going to be delayed again due to COVID, so I leaned heavily on that logic as I postponed it once more. Sure, it probably would have to be delayed again anyway, but had COVID not been around for a convenient excuse to allow me to do the row, can I say I wouldn’t have postponed the ceremony once more so I could have a bash at rowing the Atlantic? No.

Jaa, my now-wife, is a long-suffering partner. We met during my 10 year trip to every country in the world (there are 197 countries if you’re curious) so I was away A LOT. Then since finishing that, I’ve been climbing the seven summits, running marathons at the North Pole, and running trips to Yemen, Iraq, and Syria. Throughout this blog post, I’ll talk more about what I learned from rowing the Atlantic, but the biggest lesson I learned through the pain of the experience was taking Jaa, and other people close to me, for granted. So, although I’ll still try to chase my goals, I won’t do it at the expense of the people I love. The row, for all its downsides, gave me that.

So, another delay to my wedding. A p*ssed off partner. And I left Thailand to start the row. We were due to depart in mid-January, meaning I’d be finished early March and be back in Thailand in mid-March. 100 days or so away. At least that was the plan.

COVID, UK-Strains, Brexit, Customs, and Incompetence

With the guilt of leaving my girl behind, I was back in the UK with my family for Christmas. A silver lining to the chaos that my decision had caused in my personal life. Sea survival course in the south of England. Then Christmas and New Year with my mum and sister. Then to the Canary Islands (the Spanish islands where all the rowboats start their journey across the Atlantic) to meet the team and start the row. 6 weeks on the boat, then back to Thailand. But, things didn’t go according to plan.

For a start, Brexit kicked in on January 1st, 2021. That meant that the paperwork required to ship the boat from the UK, where it had just been built, through to France and driven down to Spain, had become more complicated. Brexit was brand new, so people didn’t quite know what was going on. The border between France and the UK had trucks and cargo stuck for days on end. We had hoped to ship the boat a week or so into January, and things weren’t looking good. Problem 1 was well underway.

To compound BREXIT, COVID had been proving tricky. Firstly, the new ‘UK Strain’ had broken out. That meant that countries were even less keen to allow transport from the UK. More delays for getting our boat into France, and onto Spain. Worse still was that most countries were now banning UK citizens from entering their country. The Canary Islands belong to Spain, and overnight Spain banned all flights from the UK. Sh*t.

We now had no way to get our boat to Spain, and no way to get ourselves to Spain! I had flights booked from England to Spain on January 6th. Cancelled. I rebooked for January 9th. Cancelled. Had the trip ended before it even got started?

Rowing through Hurricane Season?

Things began to get a little heated within the team. The company we were rowing with, Monkey Fist, do things a little differently from most companies. The whole logic behind this expedition was, along with raising money for men’s mental health, was to showcase their existence by partnering with Matthew Pritchard, of MTV’s Dirty Sanchez Fame (an absolutely lovely, lovely guy it turns out by the way), so they wanted to make a documentary about the row. Makes sense, fair enough.

Normally, however, when people row across the Atlantic they depart from the European side of the Atlantic in December or January. Usually, it takes 2 months to make the crossing, so that means you finish the expedition in January or February, March if you’re really slow. That was the plan for our row too, with a departure originally planned for mid to late January.

You don’t want to start any later than January really, maybe early February at a push if circumstances dictate. But any later than that and you run the risk of reaching the Caribbean at the start of an early hurricane season. The hurricane season officially ‘starts’ on June 1st, which means you don’t really want to finish in May as you’re tempting any early hurricanes. Play it safe with these kinds of things. A tiny rowboat in the middle of the ocean with a hurricane is the last thing anyone wants.

And so the issues began. As I mentioned, BREXIT and COVID were already a challenge. But to be honest, we could try to fly via Portugal or Ireland to bypass the ban on flights from the UK to Spain. It would be a little bit sneaky, but not actually illegal per se. More like bending the rules, than outright breaking them. And the Brexit stuff was in the midst of getting sorted out after the first week of teething problems. Things were looking possible once more.

However, the boat maker and the company were facing delays with making the boat-construction video, so our departure date kept getting pushed back. Early Feb. Mid-Feb. Late-Feb. Sh*t. Isn’t this getting close to at worst, hurricane season, and at best – bad, slow conditions for any type of crossing. It was so frustrating. I had wanted to get the thing going, and when the health and safety of our crew were at risk, thoughts of the bloody video were way down the list of my priorities. This should have been a sign for how our relationship with this particular boatmaker would end.

Martin and I both voted to delay the whole thing until the following December. It was getting too risky. We wanted to ensure we’d be going in good conditions. But our vote was instantly overuled. Ok then, off we go. To be delayed not because of things outside our control, but just for a film crew filming the boat being made was infuriating.

‘Illegally’ Getting to Spain, Via Ireland, To Start

Our first problem was getting the team to the Canary Islands. I had suggested we go via Ireland, and then on to Spain to avoid the flight ban. It was ‘legal’ to go to Spain IF it was work. Which for me, it was. So no legal issues.

The boat would come overland from the UK, across by ferry to France. Drive through France, into Spain, to the Spanish coastal city of Cadiz. Then ferry again to the Canary Islands.

And so off we went, armed with a mountain of paperwork. We flew from Manchester to Dublin, Dublin to the Canaries. We were grilled about why we were traveling, but after explaining our plan to row across the Atlantic Ocean each time, the officials let us through.

Landing in the Canary Islands was our last hurdle, and they barely checked our passports let alone our work status when we landed at the airport in Lanzarote. We were in. February 15th. Now we had to wait for the boat. It wouldn’t arrive for another 10 days. Our departure date was looking worrying like early March. Not cool. Was this a good idea? I couldn’t help think back to Martin and I asking to push the whole thing back to December, essentially the next year, and wondered if we’d live to regret the choices.

Impounded at Customs

We made ourselves comfortable in Lanzarote. It was my first time in the Canary Islands (it belongs to Spain so I hadn’t ‘needed’ to hit it on my journey to every country in the world). I didn’t know what to expect, but it was lovely. We had to wait 10 more excruciating days for the boat to arrive so I used my time as a kind of workation in Lanzarote, digital-nomad style. The 10 days flew by. Mostly emails and beers. And finally, Billy, our skipper and one of the founders of Monkey Fist, and the boat arrived by ferry from Cadiz. February 24th. All set to go now gents? Of course not. Yet more mismanagement, problems, and delays.

We met Billy coming off the ferry. But the boat stayed. Impounded by customs. “Mix up with the paperwork“. We were due to have sea trials the next day so this was far from ideal. And I STILL hadn’t even seen the boat, let alone step on the boat, or rowed the boat, yet!

Next day? Still impounded. Off to the customs office. Slight progress but still not released. Another day of fights and phone calls with the authorities. Who knew where the blame lay. But the following day, however, we managed to release the boat. February 26th now. That evening we packed the boat. It took hours, but finally I could see the boat, see where I’d be sleeping, how it worked etc.

The Oar’s Don’t Fit

February 27th. Getting later and later but at last, we can get the boat in the water. We organized a tow to Marina Rubicon in the south of Lanzarote where the boat would ultimately begin its journey from. Alas, to save money Monkey Fist hadn’t organised a crane to drop the boat into the water. Instead, they had hoped for calm weather and that way we could use the slip-way to drop the boat in. The weather wasn’t calm. Not by a long shot. So the boat, once more, couldn’t enter the water today.

But hey, at least I had finally SEEN the boat. I still hadn’t rowed a boat in my life yet though.

February 28th. The company bit the bullet and paid for the crane. We drove back down to the marina and the boat would, at last, enter the water this morning. ‘This morning’ soon became lunchtime. Lunchtime became mid-afternoon but, like a miracle, the crane lifted us and put us in the water. Wowzer. And we were off! Haha, yeah right.

We entered the water. No idea what we were doing (having never been on a boat before, and all that). We had a small problem with the oars, more on that later, but more important the wind, tide, and current instantly started to drag our boat across the harbour. Clueless, we smashed straight into harbour wall, nearly snapped an oar, and scraped the side of our brand new boat. A small motorboat had to come to our rescue and tow us to the dock. A little embarrassing truth be told. Not the best start.

After we were towed to the side of the harbour, it was time to take stock, and HOPEFULLY, finally, get out on the water for some actual sea trials and ocean rowing experience. So let’s whack the oars in properly this time, and maybe there is still time today even for an hour or two to experience what it is to row an ocean-crossing vessel. Great. Hang on…

Pritch and I tried to squeeze the oars into the brackets that hold them (the brackets in question are called rollicks). Something was up. They wouldn’t fit. That can’t be right, surely? Billy tries. Same issue. Are we doing it wrong? Nope. Somewhere between Monkey Fist, Avon Marina (who made the boat), and Neaves Rowing (the company who manufacture the rollicks), they had given us RIVER-ROWING rollicks, NOT OCEAN-ROWING ROLLICKS. Great job team.

What. The. F*ck. Seriously? The incompetence was costing us yet more time. So, another day we can’t get on the ocean, but this time it’s serious. Sure, we still can’t do our sea trials. But more important is that without the correct rollicks, we can’t even begin our expedition.

We’re stuck on a small island in the Canaries, where the hell are we going to get a specialist piece of equipment like an ocean rowing rollick? Short answer is that we can’t. After some brain-storming, we were forced to hire a Spanish girl based in London (remember British people weren’t allowed to enter Spain at the moment) to go and collect the correct rollicks back in England, pay her, and then fly her to the Canaries with them. And then fly her back, where she’d have to self-isolate for 10 days. All at our personal expense, of course.

That took 3 more days. 3 more days with no sea trials, 3 more days I hadn’t yet rowed a boat, and 3 days later to start our project. 3 days closer to hurricane season. I was starting to think this trip was cursed.

No Sea Trials

After our lovely Spanish girl arrived, the new rollicks DID fit and we could FINALLY experience the boat. We had yet to do any sea trials, no man-overboard drills, no sampling the gear, no working out how to make food or change shifts. Nothing. Maybe now we’d get a chance to do that. But it had already dragged on to March 4th by now.

By this point, the documentary crew was in Lanzarote with us. They needed shots of Pritch and the team rowing. This footage would then be cut into the documentary at the end. So rather than doing any of the sea trials on March 4th, we did about 3 or 4 hours of filming rowing. I did get to actually row though. My first time. Although it only lasted about 20 minutes as Pritch and Billy did all the rowing out to sea and by the time Martin and I could try, the wind was against us making it impossible to row. We were towed back to the harbour once more. Perhaps tomorrow we’ll have sea trials. Surely they wouldn’t let us go hit the Atlantic Ocean without doing some basic drills?!

March 5th. Sea trial day. Or so I thought. We rowed for an hour out to sea. My first hour. My first proper row! It felt great actually, but it was for filming purposes only. We didn’t do anything about the sea anchor, the life-saving stuff, how to use any of the equipment. Before long we were told to switch to Billy and Pritch to complete the filming, and by sunset, we were back at harbour.

“We’re leaving tomorrow morning“. Right, ok. We hadn’t packed, it was already 7pm and we had a wake-up call at 4.30 am. No sea trials, very little time to prepare to leave on the journey of a lifetime, and now the Spanish girl had arrived I had given her my room in the villa. So, my last night on dry land was spent sleeping on a couch out in the open, instead of in a bed. Wonderful. We got to bed around 1am, giving us less than 5 hours sleep before the hardest few months of my life.

The next morning, the early wake-up came and went, and we drove to the marina to set off.

Starting the Row and Getting Rescued

5am departure, it was still dark when we arrived at the marina. There were some media at the dock, but to be honest i would have preferred a quiet, humble exit. I was nervous about what was ahead. And taking pics and answering questions was the last thing on my mind. Finally, after months of delays, mistakes and issues, we were actually going to start this thing. It seemed surreal.

The sun soon rose, and with that, the clock struck 8am. We were finally off. Pritch and Billy were the duo to get us started. Martin and I retired to the cabin, and that was that. Rowing out of the Marina Rubicon, Lanzarote slowly getting further and further behind us. The waving arms of people soon became indistinguishable. Then the buildings disappeared and the shoreline merged, until the island was just a large mass. We shouldn’t be seeing people, or cars, or ‘stuff’ again for months. This was it.

After the first 2 hour shift, Martin and I hopped into the rowing positions. And we began our first shift. It was probably the last shift that I could honestly say I enjoyed. It was exciting. I had invested so much into this expedition. Time, money, relationships. And the thing had seemed doomed to fail. It felt like it would never get off the ground. But nope, we did it. Resilience, stubbornness, stupidity. Whatever it was, we were actually rowing. The Atlantic was in front of us. And Antigua would be the next time I would stand on dry land. Or maybe not.

From 8am until sunset, around 8pm, things were good. 2 hours shift rowing in the sun, 2 hours resting. Getting to grips with how the shift changes worked. Trying to find the best spot to sit, the optimal level of exercise vrs comfort. It was a little bumpy but no sea-sickness was apparent, although I didn’t eat anything all day. Nor did any of the boys. So our bodies knew that something was up. But the vomiting was kept at bay.

The sun soon set, and the Canary Islands were still eminently visible. Lanzarote behind us, then Fuerteventura to our side. Slowly disappearing just as Lanzarote did. As the night fell, I had my first negative thoughts. The first of many to come in the following months. The weather picked up. Before long the waves grew, and within 30 minutes the sky was pitch black. Suddenly we were getting wet. Waves smashing us from the side constantly. And it was cold. Really cold.

I came on to another night shift around midnight and I had to wear a t-shirt, hoody, and large ‘bad-weather’ coat. Shivering, I had to row hard just to keep warm. Every time I built up some steam, I got smashed by freezing cold saltwater. A wave smashing against the side of the boat, ‘the beam’. I hadn’t worked out how to wear the foul-weather gear properly (no sea trials, remember?!) so I was drenched. Soaked to the skin. So each time my shift ended, Martin and I clambered into the cabin and tried to sleep, fully clothed in our seawater-drenched cotton hoodys.

I didn’t sleep a wink. I lay on my back, soaked in salt water, the boat rising and falling with each wave. The cabin was covered in sea water already on day 1. Sleeping bags? Soaked. The mattress? Soaked. And it hadn’t been fitted properly so we were sleeping directly on the hard plastic floor. Sea-sickness had hit and all-in-all we were miserable. The 2-hour break would end, and it’d be our turn to row again. Slipping on my soaking socks and sneakers, squelching my toes in tight, I thought “Wow, this is grim, did I expect it to be this horrible!?”. Anyway, get it together johnny boy. It’s your turn to row. And the rowing continued.

Sea-sickness now. The waves had picked up further still. So on my first night, as I was rowing, mid-stroke I was vomiting over the side of the boat. Then back to rowing. Then vomit, then back to rowing. Ooooph. A newfound respect for the people who have actually completed this Ocean rowing emerged. This isn’t fun at all. 3-night shifts continued like this. Soaked right through, and each time I retired to the cabin, I would lie on the hard floor, shivering and wet. staring at the ceiling until the 2-hour ‘break’ was up. And then continue once more.

At the end of the 3rd night shift, I opened the hatch and the sun had risen, and the waves subsided. Thank god. Still soaked, still freezing, but we had survived night number one. Surely it can only get easier from here.

The Boat Falling Apart

As soon as I opened the hatch, I was ready to swap positions with Pritch. “How’s it going Pritch?”. I asked through gritted, shivering teeth. “Errm, not good“. Billy was on his hands and knees, hacksaw in hand, fiddling with something around his seat. Not a good sight. So what happened?!

When you row an ocean, the 2 rowing seats are on small rollerskate-esque wheels, so they can slide back and forth with each rowing stroke. Allowing you to generate more power. The little seats, and their wheels, sit and run along a kind of L-shaped bracket. All good. Our boat company, which MonkeyFist had partnered with for some kind of freebie/test-run, had NEVER BUILT AN OCEAN ROWING BOAT BEFORE. They had made that runner out of some weak carbon fibre thing. And if you remember, WE HAD NEVER EVEN TRAILED THE BOAT ON WATER ASIDE FROM A COUPLE OF HOURS FILMING, so we didn’t know if it was ocean-worthy or not. Turns out it wasn’t. The runners had started to snap, after less than 24 hours at sea, the boat was breaking down. We could still see some of the Canary Islands in the background, so what could we do?

To make matters worse, in the center of every ocean rowing boat is a little hole. You can actually look down through it and see the ocean. When the weather is bad, and the wind and waves are hitting you right on the side of the boat, you stick something called a ‘Daggerboard’ down the hole. It sticks out the bottom of the boat about a meter or so and stabilizes the boat a little. It stops you from wobbling side to side so much. After a night of awful weather, we had to stick the daggerboard in to keep us steady.

Now the morning had arrived, the weather had cleared up. You don’t want the daggerboard in when the weather is good as it adds resistance to the boat. And it slows you down. So we try to lift the daggerboard out. Nope. Stuck. Impossible to get out. And in trying to get it out, we use one of the ‘unbreakable oars’, and snap one of the oars. We had 6 oars to start with. 4 to use and 2 back-ups. Make that now just 1 backup.

So, the daggerboard is permanently stuck in the boat, the runners have snapped, we’re down to one spare oar, and we have had to call the Spanish coast guard to rescue us. Not a great first 24 hours to be honest. After a miserable night, what more could go wrong? Well, at least the insurance will cover the rescue right? Right? Oh, turns out we the company never got insurance for us. Perfect.

Getting crashed into. More Damage.

After the call to the coastguard was made, Billy and I threw out the para-anchor (like a parachute in the water) It stops you from drifting anywhere, and acts like a normal anchor. This way the rescue vehicle will know exactly where we are. About 4 hours later, the cavalry arrived. They didn’t have any experience with ocean-rowing boats, fair enough, it’s an odd situation. Not understanding that we have no motor and therefore can’t stabilise ourselves, or move out of the way quickly, they drove their huge motorboat right over to us. Billy was screaming for them to get back, their massive motors were right beside our para-anchor, and could have sucked us in.

The waves picked up, and rather than rescue us calmly, they smashed their huge boat into our rowboat. The noise it made was excruciating. Creaking, bending aaaaand… snapping the front panel. We pushed them back, but another wave came and this time they smashed us again, but this time it actually cracked our cabin, leaking water and now making us no longer watertight as a vehicle.

After a lot of shouting and screaming, we attached a tow rope and began the tow back to the Canary Islands just after midday. The damage done by the rescue vehicle was worse than the actual damage that caused us to call them in the first place. The expedition looked over. And the tow began. It took us over 7 hours to be towed back to Fuerteventure island.

We were drenched. Bouncing up and down on the water for 7 hours, waves piling in. I was stuck, alone, in the luggage cabin at the front of the boat. Eating every wave and getting thrown up and down in the air each time we hit a bump. The other 3 guys were in the sleeping cabin at the back. 7 hours later we arrived at the port, soaked, freezing, bruised, and disheartened. One of the worst experiences of my life. And although it’s shameful to admit, after what was probably the worst night of my life rowing, and now with the boat breaking down, I was quietly thinking to myself “I hope the boat is too badly damaged to fix, and this thing is called off“. That would give me a ‘valid’ excuse to not continue. Pathetic, but true.

We clambered onto the dock in darkness. All 4 of us, hobbled together. We’d sort out the bill and assess the damage tomorrow, but tonight we had to find somewhere to sleep. After a few frantic phone calls, and with all of us at the risk of hypothermia, we managed to find an Airbnb within a couple of hours.

A Week in Fuerteventura and more problems with the boat

That week was actually pretty fun. For a start, it was a relief to be off the boat. We moved into an apartment near the marina where the boat was going to get repaired. The first morning we ran down to the boat to assess the damage. After a shower, and a sleep, spirits were a little higher. Still, looking back at the night that just passed, thinking about the huge waves smashing me as I rowed, soaked, freezing, the whole thing didn’t seem too appealing to me.

Once we got to the dock, we could see the daggerboard was still stuck and not going to budge, and that the seat runners were definitely not adequate for crossing an ocean. And there was a pretty bad leak from the collision with the Spanish coast guard. How long would we be here? We hoped a day or 2, but deep down we knew it would take a while. Every day we were stuck there though was another day delay, and another day closer to hurricane season, and another day further away from the normal rowing season.

I was so frustrated with the boat manufacturer. We hadn’t heard a word from them since the boat began to break down, aside from them denying that they had made any mistakes. They told us it was impossible for the daggerboard to be stuck, and that the runners must have broken due to us jumping up and down in waves and thereby applying too much pressure. How on earth they thought we’d row across the Atlantic without waves hitting us for months went beyond my scope, but here we are. I was thinking that perhaps an apology, some empathy, even a direct message, or phone call, to each of the 4 of us rowers would have gone a long way. But no, nothing. Yet we were stuck once more, with the season getting later and later.

Day 3 of our time on Fuerteventura we finally found a carbon fiber expert to work on the daggerboard and cracks in the boat. Progress.

Day 4 I found us some stainless steel to use instead of the ridiculous runners the boat company had created.

Day 5 Billy and Martin expertly fitted the new runner, and everything was almost finished. But because Monkey Fist had no insurance, we owed the Spanish Coast Guard about $3,000USD. I (not-so) politely suggested we send the bill to our lovely boat-builder, it was their incompetence that caused this.

Since finishing the row, I learned that Monkey Fist had sent a kind of begging message to the WhatsApp group our loved ones were in. “We owe $3k, and we don’t have any money…” or something along those lines. Let’s just say our families and friends weren’t best pleased with the hopeful suggestion that they may foot the bill. Not a good energy.

Another social media post was published on Monkey Fist channels stating that they had had no money in their accounts, and no insurance and were now in debt to the Spanish Coast Guard. And a kind gentleman came forward and stumped up half the cash. We hung around for the rest of Day 5 and 6 to see what was happening, but eventually, around 8 am on Day 7, a week later, we set off again. I’m not sure if that bill ever was paid to be honest, but at least we were setting off again.

Starting Again, A New World’s First!

The one positive to take from all this madness was that no-one had ever rowed from Fuerteventura to Antigua before, so if we managed to complete the row (and who knew if we could based on what’s already been going on!) we’d automatically set a new world-first, and world record. Cool, but just a bit of fun. As I mentioned above, most rowers leave from the islands further West of either Lanzarote and Fuerteventura as it’s ridiculous to add a few 100km to your row by starting even closer to Europe than need be. Still, the company got a free dock to leave from, hence the decision to leave from Lanzarote and not an island closer to Antigua.

Finally, we were off. The team’s morale after a week on land was definitely higher. Each day while we waited in Fuerteventure we all got to grips more with what would be required to pull this thing off. We packed the boat better, and finally got a vague idea of where stuff was packed. Although there wasn’t much of a system to be brutally honest.

Still, though I had no idea about how to use any of the survival equipment, the stuff you use if you find yourself overboard. And still, we had no idea how to use the life raft, or do any man-overboard stuff. We hadn’t learned how to use the GPS/satellite systems either, so if something was to happen to Billy, our skipper, we’d be in real trouble. With that, we hoped nothing would happen to him, and off we went.

The worst month of my life

So, the actual row. How was it? In short, the worst experience of my life. But admittedly, not one without benefit. Although I did have to wade through what I can honestly call misery before I came out the other side and could see the light.

Before signing up to do this thing, of course I had thought about the lack of privacy, the isolation, the discomfort, and the actual rowing. I thought I had got my head around it. I had mentally prepared myself for 5 or 6 weeks of hard, physical endurance. But now through all the issues above, we were way out of season. The damn thing ended up taking us into our 8th week. 50+ days, just shy of 2 months. Pretty grim.

So not only was the experience far more difficult to deal with emotionally than I ever could have imagined, but it also took much longer than we all had planned and hoped. I find it quite hard even to write this blog post in all honesty, which is why it’s so late after finishing before it’s published.

I was relieved to finally leave Fuerteventura. It had been over a month since saying goodbye to mainland Europe, and to finally set off was a huge moment. And this time, the boat seemed ready. We were also more prepared.

Day 1 of our second attempt at rowing across the Atlantic. 2 hours on, 2 hours off. 24 hours per day. It wasn’t AS bad as the first 24 hours a week ago, when the weather was horrendous, and we were soaked, trying to sleep. This time the weather was kind. And calm. I knew what to expect, and after such a stormy, windy introduction, this was much easier. Perhaps this wouldn’t be so bad.

My spirits were pretty high that first day, truth be told, but it wasn’t to last. By the time day 2 ticked over, and I woke up for my first shift of the 2nd day. Reality bit. This process would go on, not for days, or even weeks like some of my previous expeditions. But months. Literally months. Waves of panic struck me. I have never experience that hot flushing, heart rapid-beating, hyperventilating type of panic before. I would experience it each and every time I tried to rest. So the actual 2 hours of rowing wasn’t so bad. I could row hard, and lose myself in the exercise.

But each time I came off shift, made my food, and lay down. There it was again. Deep dread, and regret. Always seemingly on the cusp of a panic attack. I was stuck in this tiny boat, for MONTHS. I couldn’t escape the emotions. Often a tear would roll down my cheek, and I’d turn my back on Martin to avoid him seeing. And I’d lay there pretending to sleep, so regretful for signing up for this torture. Leaving the life I had created for myself, leaving Jaa, leaving my healthy food and beers with the boys. Leaving netflix, and daily calls to my mum. And for what?

The cabin was so small. You couldn’t even sit up properly without heavily hunching your back. Imagine 4 guys living under your kitchen table. It was like that. Often you’d forget and crack your head off the random bolts that the boat-maker hadn’t covered, or forgot to remove. Often drawing blood. Shout out “Motherf*cker“, wipe the blood and carry on with whatever it is you’re doing. Rinse and repeat. Day 2. Then Day 3. Day 4.

Was the dread alleviating with each passing day? Far from it. I felt it accumulating. Building up. I was in constant anxiety and felt consistently at risk of having a full-blown panic attack. I was relieved to get on the row shift each time, it was the only time I felt a little free. But being cooped up in the cabin, I was slowly losing my mind.

The normal complaints from other people who had rowed oceans didn’t bother me. The food? It was fine. More than fine actually. Dehydrated food that you eat by adding boiling water and leaving for 5 minutes. Kinda tasty actually. The exercise? Enjoyable. Using your lungs, heart, and muscles. That’s what I signed up for. I wish we rowed harder if anything. The sleep deprivation? I mean, sure, it’s not ideal. But it wasn’t something haunting me. We could carry on.

But the claustrophobia? The isolation? The lack of personal space and privacy? The never-ending dread of negative energy that there is no end in sight for months? That weighed so heavily on me every single second. I couldn’t escape it. I tried meditating. Tried sleeping. Tried listening to books. Music. Tried chatting to the team. Nothing helped. And I didn’t want to be a negative energy source to the expedition, so I kept the true depths of my unhappiness to myself. Literally not even admitting anything like that until near the halfway point, by which point, whilst still miserable, I had at least got through a month.

The lowest point

I struggled with sleep. I was so miserable that anytime I lay down, my mind would drift to how long I was stuck here. It was a rookie error. Focus on the bite-size chunks, that’s the key, always. But I couldn’t. I kept reverting back to the sheer length of the trip and how unhappy I was. And so I couldn’t sleep. Until finally, around day 10, I fell asleep during a rest shift. A proper sleep. REM sleep. Finally. Martin had to wake me up to tell me our row shift was starting. And as he woke me, I was disorientated. I didn’t know where I was. Assuming I was in my home in Thailand or visiting my mum in Ireland. Content, for just a brief second.

And then an instant pang of pain. I had a sinking, shooting pain in my heart and soul when it dawned on me where I was. On this f*cking boat. For months to come. In about 3 square metres of space. I was broken. All I wanted was to get off, but there was no escape. I wiped a tear away, and off to the row shift I went. Brutal. One of the lowest, if not THE lowest I’ve ever felt in my entire life.

Pulling Your Weight

And then there is the big question about how long it’s going to take. I had hoped we’d be running for world record pace. I know I can dig deep, Matthew Pritchard is a beast (10 iron men in 10 days etc), and Billy, despite not being traditionally ‘fit’, was a hugely experienced rower. His technique was twice as good as mine and he’s a guy who gives it his all. I knew Martin, at 62, wouldn’t quite be as strong. And to be honest, if I’m rowing oceans at 62, I’d be surprised, so massive respect was due there too.

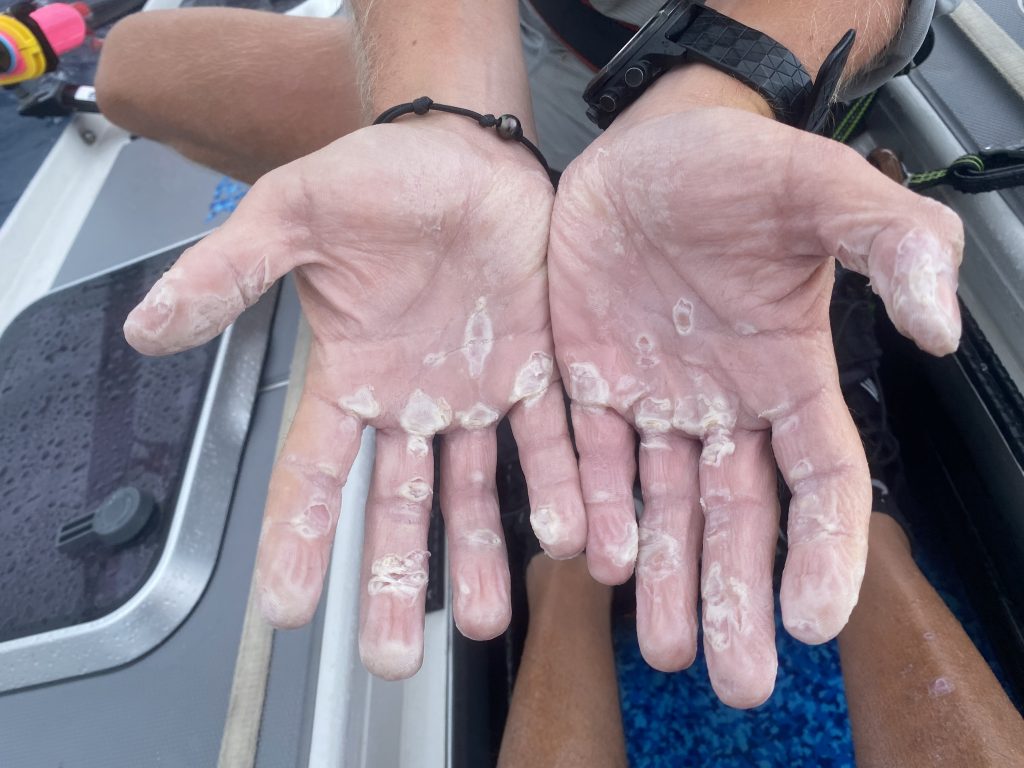

With Billy and Pritch being in a pair, I could see during each of their 2-hour shifts, they were out-rowing Martin and my distances every single time. I felt so guilty. Were Martin and I pulling our weight on this thing? Probably not. And I felt so bad. I’m sure the boys were thinking we were slowing them down. Well, we were. That ultimately meant we would be spending extra days (weeks?) at sea. I was doing the maths after every shift, working out the differentials, and calculating how many days we were adding to the expedition by not matching Billy and Pritch. So I was trying so hard to match their statistics on each shift, killing myself, ripping my hands to pieces every shift I sat down. And that’s when the first bit of friction occurred. And shamefully it was all my fault.

During each session, I was dripping with sweat. I couldn’t open my fingers wide because they were locked in a claw from gripping the oars so tight. I was determined our pair should at least endeavor to match Pritch and Billy’s output. Even if they’re stronger than us, we can at least match their effort, if not their output. So let’s try our best. Simple as that.

Martin and I had been taking it in turns as to who sat in the front and who sat in the back. The ‘stroke seat’ is the seat in front. It’s called the ‘Stroke Seat’ as it sets the pace, and the rower behind has to match the pace and stroke rhythm of the front-rower.

When I was in front, we could just about match their pace. It was tough, but if I killed myself each time, we could just about match them. When I was in the stroke seat, upfront, I couldn’t see what Martin did or didn’t do. I could, however, see that he wasn’t synchronized with my stroke. Essentially, he was doing his own thing in the back, and although I know almost nothing about rowing, I know that’s a super inefficient method not to match your strokes in a pair. I tried to ask him gently to match my strokes, but he said he can’t spend his whole time fixating on stroke speed. And what that, I didn’t want to push the issue any further.

I could also see the nautical mile counter. That meant that I knew what the other team did in each preceding 2 hours, and I tried to make sure we got as close to that as possible. However, when we switched and I was no longer in the stroke seat, our output plummeted. Up to 50% sometimes. I would watch Martin’s oars for every stroke for 2 hours, trying to make sure I was synchronized with him. There was no real rhythm, it was erratic, each wave would come and the stroke length and distance would change. It is tough work to keep a consistent stroke length and speed during the waves, but if you brace yourself and dig deep, it’s just about possible.

Although it takes a fair bit of effort. Martin would allow the waves to control the stroke instead. And I would try to mimic Martin’s random strokes. Full concentration. It was mentally knackering. But the boat is so small, and I didn’t want to cause any further conflict.

So for the first 2 or 3 weeks, I kept my mouth shut. I was desperate to suggest that we try to always ensure we’re synchronized. That we kept consistent stroke speeds and lengths. And that we try our best to match the output of the other pair. And that, of course, we are all different levels, but we can all make the same level of effort. But I was getting on so well with Martin socially, I couldn’t bring myself to risk any animosity with him. And with that, I kept schtum for as long as I could.

On my shifts at the front though, I would try to set an obvious level of effort, and pace. I tried to subtly refer to the mile-counter, to goals, and I would mention how it was tough it was for me to work this hard, but this is what we’re here for etc etc. But it fell on deaf ears.

I could feel the frustration in me building. The boat is a pressure cooker, but one with no release. So when I didn’t see a bead of sweat on Martin’s body for the first 2 or 3 weeks, it was tough. Especially as I was killing myself every single shift. And when I watched and chatted with Billy and Pritch during their rowing shifts, I was so jealous. They both tried their best to row in sync, they both tried hard, and dug deep. I longed for someone to row with me with the same effort. To dig deep. Why wasn’t Martin pushing himself?

Eventually, I broke and I brought up the issue. Roughly around week 3 or 4. I was gentle. Or at least gentle by my not-so-subtle Irish ways. I know Martin was older, and I know he didn’t come from any kind of fitness background. He’s not a gym-goer, and he hadn’t experienced any endurance races or expeditions before. People are different. But everyone can offer the same level of effort, regardless of what kind of output that level creates, right? That’s what I was trying to note. He snapped back “I am working hard, I am trying my best, I am working as hard as I can“. I couldn’t understand it. How can that be ‘as hard as I can‘ if you’re not even sweating? Not breathing any faster than a walk on the beach? I didn’t know where to turn.

Martin soon requested to only sit in the back seat. It’s the ‘easier’ seat. The waves don’t hit you as much, you have a little more privacy because everything is in front of you. I was sad to think I would no longer have that escape. But ok, if it makes it better for Martin, let’s do it. That way he was permanently behind me. I could now no longer see what level of effort he was putting in. That was frustrating, but perhaps it would be a blessing.

But the pressure cooker remained. On each of our 2-hour sessions, I’d be rowing solo for the first 10 minutes of each shift while Martin sorted out shoes, or phones, or sunglasses. I’d be rowing solo for the last 5 or 10 minutes each shift, while Martin tended to sunscreen, or snacks, or laces. He’d take his toilet breaks during row-time, not during break time, giving another 10-minute break here and there.

Such innocuous things on the surface, but my mental state wasn’t good and it was eating me up. I felt like I was rowing our shifts almost solo. I could feel my frustration growing again. Every day I was in more and more pain. I would be sharing war stories with Pritch and Billy, our hands falling apart, red-raw from blisters. Martin’s palms looked like he’d been tending to the garden on a sunny afternoon. But right there and then, through Martin’s calm demeanor, and lovely personality, I had a good long look at my selfish self. I had a bit of an epiphany. And it marked an upward turn in the whole experience, and I hope in my future life.

An epiphany

I had signed up to push myself physically. I wanted that emotion where you dig deep. You suffer, and have dark thoughts, you’re in pain, but you battle through. And I was frustrated that Martin’s hands looked like he hadn’t rowed a stroke, I was frustrated that his hands weren’t aching. I was frustrated that he wasn’t hurting like I was. And that this speed would add days to what was already a horrible experience.

And then I learned the most important lesson of the whole row. Martin Heseltine wasn’t on Johnny Ward’s expedition.

Martin had seen plenty of old boys row an ocean over the last few years. And in fact, a 70-year-old had, just 3 months previously, broken the record for the oldest person to row an ocean. It took him 60 days or so. The same with the youngest female to row, she too had recently finished.

The secret truth about ocean rowing

The secret truth about ocean rowing, which ocean rowers don’t like to broadcast, is that if you row the Atlantic in the peak season, leaving in December, even if you don’t row, or barely row, you’ll get across the Atlantic in about 60 days or so with little to know effort.

In fact, people have drifted across the Atlantic in rafts WITH NO OARS in about 60 odd days. Just with the help of ocean current, the swells, and the wind. If anyone does it in peak season in and around 70 days or more, the elements have pushed the vessel across, not the oars. A vessel in which they have resided. The ‘accomplishment’ is being cooped up and enduring the misery, not the physical achievement. The ocean rowing society won’t appreciate me whistle-blowing, but there you have it.

And Martin, having seen that, was more than entitled to think he could enjoy the experience, row when he could, rest when he needed. Why not?! It’s still an adventure. You still cross the ocean. He didn’t sign up to kill himself. He didn’t sign up to row with the effort, or output, of anyone else. And if that was his maximum level of effort, then that’s his maximum level of effort. I had to accept lots of people have no desire to get dark and suffer. To see how far they can push it. And they’re probably much more relaxed about life living in that gear. Without the pressure, I seem to pile on myself.

So the problem wasn’t Martin’s effort or output. The problem was mine. My attitude. My arrogance, My demons. 100% mine. Martin wasn’t on my expedition. He didn’t sign up to MY expedition. I can push as much as I want. As could he. And so we did. With that new mentality, the friction disappeared entirely. I continued to kill myself of course. Forcing my body to breaking point. I managed to match Pritch and Billy’s output on most sessions. And Martin could do what he wanted in the second seat. And with that, my relationship with Martin flourished.

We had always got on well. I was always hugely grateful to have his calming energy on the boat. A kind, gentle soul. We would have discussions about theology, politics, literature late through the night. I would have gone insane without those chats. And despite my early frustrations with his rowing, I love the man. And couldn’t have imagined the row without him. But once I rid myself of my frustrations, it was better still. Like a father figure for me on the boat. I cursed myself for getting so worked up at him in those early weeks.

So if you’re reading this Martin, I’m sorry mate. I’m sorry for being grumpy. I’m sorry for doubting your intentions. And, I’m sorry for being an ass. You’re a gem. And I was lucky to have you as a row partner. I was a lot more blessed with my row partner than you were with yours. And most of all, thank you for the life lessons.

No Life Raft

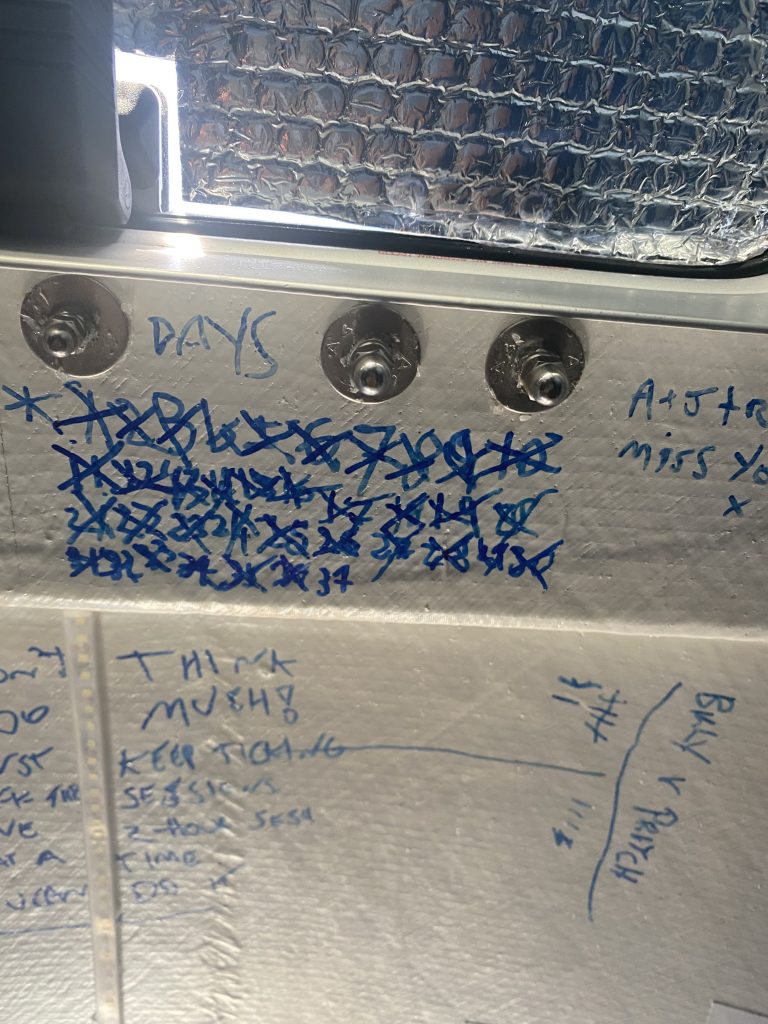

I got through that first month. Not by any trick, not by mindfulness, yoga, or breathing techniques. Just by attrition. “This too shall pass“. I repeated that mantra countless times. Tough periods don’t last forever, however tough. I did my 2 hours on, 2 hours off. I recorded every shift on the wall of the cabin, like a prison sentence, and slowly, very slowly, the shifts mounted up. Month 1 done. Bring on Month 2. Let’s do this motherf*cker. And then another discovery struck us.

Martin was an experienced sailor too. This was helpful considering Pritch and I knew so little about anything ocean-orientated. We were around the mid-way point on our row one sunny afternoon when Martin discovered our latest issue with our not-so-wonderful ocean rowing vessel. Essentially, we had no life raft.

I was in front, on the stroke seat, with Martin behind. At the break-time, Martin asked me to spin around and have a chat about something. “Yes mate?”.

Now, the life raft was in an emergency compartment in the middle of the boat. Underneath where we sat to row. All good, right? Wrong. The way the compartment had been designed meant that in order to access the life raft, someone would have to go and locate a spanner from the cabin lockers, bring them out, find the correct sizes, and then proceed to unscrew and unbolt 2 entire footplates. They’re permanently fixed to the floor to allow us to get some purchase as we row. Ridiculous. The process could easily take 5 minutes or more in calm weather.

The only time we would need the life raft would be if the boat capsized and was sinking. The normal plan in that scenario would be one of the four of us would urgently grab the raft, chuck it in the ocean and hop on to it to save our lives.

For that scenario to arise, we would most likely be in a huge storm, with 30 feet waves. Getting battered to the extent the boat broke down. With a 50% chance of it being at night, in pitch black. For us now, at that moment, we’d have to get into one of the cabins, find the toolkit, get the toolkit out, find the correctly-sized spanner, get on our hands and knees and unscrew one footplate, then maneuver ourselves to the other footplate at the other end of the boat, all while the boat is upside down and underwater, in the dark, with 30-foot waves? Sure. Not even remotely possible.

Remember, our loving boat builder had never built an ocean rowing boat before, so they hadn’t thought about it. At this point, we were now essentially rowing without a life raft. When the big waves came, and they did come, I was constantly thinking that if we go over, or under, we’re dead. Add that to the anxiety pile Johnny boy.

Depression

I’d have brief periods of being just about ‘ok’. Capable of having conversations in little 5 or 10 minute bouts. But without fail my mind would revert back to me considering how long I was stuck on this thing, this perpetual groundhog day. This never-ending nothingness. And some form of depression would once again slip back in.

With other endurance experiences, there is always joy to break up the pain or suffering. High altitude mountains, ultramarathons, whatever it is. You can often end up in hospital due to the damage you’ve done to your body, but the joy of the experience outweighs the negative side. Pretty much always. But here? There was no joy. Just repetitive nothingness. And misery.

Occasionally I’d hit rock bottom, or at least I thought I had, only to find out that bad weather is coming and your progress will be slowed to almost a stop. And you realise that rock bottom wasn’t rock bottom at all. Because the weather now means you’ll be on this another extra day, and another, and another. It doesn’t get any worse.

Half-way point

The days passed. Slowly. It was hard to distinguish shift from shift, day from day, even week by week. Everything was just on repeat. No wildlife, no fish, no birds. Same food, same routine. It’s such a strange sensation in all honesty. On one hand, it was most definitely the longest 2 months of my life, but in the same breath when I look back, it disappears in the click of a finger because nothing really happened. It just seems to be one big grey cloud.

There was a 4 week period in the middle of the expedition where we didn’t see ANYTHING. For a whole month. Not one boat, not any wildlife, not even a piece of trash. Just blue. Blue skies, and blue seas. It’s truly difficult to explain what that does to you mentally. Being void of any and all stimulus for a prolonged period of time. And all the while, not sleeping more than 45 minutes at a time, and never standing up, or taking a step. I’m pretty sure it’s awful for you. Physically, it’s clearly damaging. Our hands were breaking down, our skin too. But it’s mentally where I was struggling. We were raising money for men’s mental health, and I was left wondering if ironically that ocean rowing is awful for my own mental health. I had never been so low.

We reached the half-way point. A point where I hoped my spirit would lift. But it didn’t. If anything I felt worse. I had been truly miserable for so long, for over a month. And the thought of doing exactly the same duration again was soul-destroying. I felt incapable, yet there was no way off. Not good.

I had been disciplined in terms of calling my loved ones on the satellite phone. I promised myself I wouldn’t speak to anyone on the phone until the halfway point. The distance between where I was mentally, and the happiness that connecting with loved ones represents was a void too big to bridge. It would have made me worse. Finally, at the halfway point, I allowed myself weekly calls to Jaa and my mum.

That helped. I had about another week until we reached the main checkpoint, the 1000 mile countdown. We all just had to dig deep and get through another week or so until we got to that magical 999mile countdown. It would be a seminal moment. I introduced chocolate puddings into my diet as a celebration. Anything for a pick-me-up. And it worked. I ended up relying so heavily on the emotional uplift from chocolate puddings, I honestly think I actually PUT ON weight in the 2nd half of the row. Now that’s got to be some kind of world record.

Occasionally, much to the amusement of the team, I’d double whammy 2 chocolate puddings, AND cut up a mars bar and add that to it. Equalling a whopping 1500 calories for breakfast!

1000 miles to go

The whole expedition is approximately 3000 miles/5000km. And it can take up to 2 months. As I said, the first month was undoubtedly the worst month of my life, I had never felt so down. Regret for signing up and being away from my loved ones, angry at myself for the money I had spent on this experience, and frustrated at the boat builders and organisers that caused the chaos to delay us further still. I also felt that this negativity would never let up. But it did. I guess it always does?

Somewhere between the halfway point and the 1000 miles, we finally got to swim in the Atlantic. We only did it once. You need to wait for the conditions to be calm enough to get in and out. And also any time you spend in the ocean is time added to the expedition, so you don’t want to mess about. So it’s not a common thing. Although it felt amazing to get out and lather up, soaping myself down for the first time in 5 or 6 weeks was heaven. And swimming in a piece of the ocean that no one had ever swum in before was a privilege too. Albeit a scary one with 5000m below you and in the knowledge that if you get swept away, you’re gone forever.

We reached a HUGE point. I knew it had been coming. I was breaking down every single 2-hour shift into tiny percentage gains. Counting the minutes, and ‘1000 mile to go’ was my first significant benchmark. It also meant we were past the 2/3rds mark. For me, that was so much more powerful than the halfway point. To know I only had to do half of what we’ve already done to reach the finish point was genuinely motivating.

I couldn’t quite say the end was in sight, but for sure it was the first time I contemplated genuinely finishing this thing. We had about 3 weeks to go. I broke it down to 2 sets of 10 days. Telling myself, just get through 10 more days of this suffering, and you’ll only have 10 days left. You can do 10 days, right? Bite-sized chunks. Always.

And the home straight wasn’t without adventure. Storms hit, crazy squalls where visibility dipped to about 3 or 4 metres in front. Ice cold rain beating down on you from nowhere, and then silence. Occasionally a storm front would move in, and hit us with sky-scraper size waves. Twice I thought we would capsize. The wave hitting us from the side, teasing the boat, tempting it to flip, up on its side. Martin and I flung off our seats, but clipped into the safety harness, Will it? Won’t it? Will it? And then twice, thankfully, it fell back in place. No capsize today. And on we’d row. Barely even a second between the fear of flipping and restarting rowing. That’s the nature of the beast. 900 miles to go.

Lessons & Comfort Zones

Finally, I broke out of my depression. I was still pretty over the whole thing, but I wasn’t in a full, dark place any more. No more tears out of nowhere, no more self-loathing. I still wanted off, but this time I wanted to get off in Antigua.

At this point, I could start to appreciate the lessons this brutal journey was teaching me. I had already realised my arrogance with my assumptions of Martin’s row. A tough mirror to look into, but I had days and weeks to keep staring into. I had processed it, absorbed it, and learned from it That lesson will never leave me.

But also I had a newfound appreciation for the life I had created for myself outside this boat. I was always racing from one goal to the next. Finish one, onto the next one. Not for one second did I appreciate the little things. The coffees with loved ones, the phone calls, the laughter. Or on a deeper level, the security, the safety, the financial freedom. Never would I take that stuff for granted as I had been doing. What’s the point in pushing yourself, to just then push yourself harder. Surely there should be some enjoyment? Some reward? Both for myself, and the people that support me? I’m going to try to ensure that.

Family, suddenly, became more important to me. I’ve always been close to my mum, and sister, but I found a deeper desire to have a closer-knit community around me. I’ve always tended to be independent, almost a loner at times, off around the world chasing whatever thing I’m chasing, but being solo by default on the boat flipped that on its head for me.

It was a privilege to have the opportunity to reflect on my life, my mistakes, who I am, and who I want to be. To have that much unadulterated time to look at yourself, and your weaknesses is kind of unheard of in modern life. We can read books, meditate, convince ourselves that we’re taking time out and time off. But life comes at you fast and before you know it, you’re back in the game. But on the boat, there’s none of that. The game is weeks, months even, away. So you can’t escape those thoughts, neither the good or the bad.

And then it got me thinking about integrity. I always like to think I push my comfort zones. And then through my blog and social media, I truly hope I help encourage others to push their comfort zones. You don’t know yourself until you’ve been dark and had to dig deep. That’s true.

However, was I pushing myself these days? To my maximum? Sure, the ultras, the mountains, the ‘every country in the world’ thing, they have been tough and they required a lot of commitment and sacrifice. But in a way, they had become part of my comfort zone. To suffer through those particular channels. Many times I had the opportunity to join meditation classes or silent retreats. But I always turned them down. Scared and anxious about my own thoughts. When I try to sleep at night, I overthink things. Get stressed out. Imposter syndrome is real, anxiety-ridden about whatever trip I’ve planned to rake people on, or how to finance my new family home.

Anyway, the thought of having to address my weakness, anxiety, and demons in a silent retreat? F*ck that. So I never did it. Always said no. And I never considered about it, but that made me a hypocrite. Extolling the virtues of escaping comfort zones, yet running from the one thing that would push mine? And then the row came along. I thought I was signing up for a physical challenge like no other. To extend the same comfort zones as I had been doing. Little did I know, I was signing up for a different challenge altogether. A week’s silent retreat in Thailand? I turned it downtime and time again. Afraid.

But now, I had accidentally signed up for something akin to a 2-month silent retreat! And it was f*cking tough to deal with. So now, ironically, I don’t think I’d struggle so much with a week’s silent retreat! Where do I sign up?!

Finishing the row

The last 20 days felt better. Still a drag, and admittedly, the second month on the row boat was still probably the second-worst month of my life, but it was a vast improvement to the first month. And with each day, the finish line became a more realistic prospect in a way that, during month one, it never did. What was once a seemingly endless, relentless pursuit, suddenly became tangible.

Where I once thought that the ocean was relentless, the waves were relentless, the routine and schedule were relentless, and that all of those things had the prospect of beating us. In those last 2 or 3 weeks, I realised that those things were merely consistent. But in fact it was us, our team, our boat that was relentless. Regardless of the obstacles, of the weather, of the chaos, we showed up for our 2-hour shifts every single shift. In fact, Martin and I didn’t miss one shift the whole time. We were relentless. Us. Our expedition was relentless. And finally, that relentlessness was paying off.

Until sunset on day 50, a squiggle, a shadow, a dark outline. Antigua baby. Squint in the right direction, you can see it. Euphoric.

Our first sighting was just at nightfall. We rowed all night, in pitch black, our last night. And when I went to the cabin around 4am for my 2 hour break, I would re-emerge at 6am. The sun had risen. And there was Antigua in all its glory. Big and beautiful. AND GREEN. Lush green. Rainforest GREEN. I hadn’t seen colours for months. I was ecstatic. And relieved. I wasn’t ready for the outpouring of relief about truly seeing the island. Sure we could see it in the far distance last night, but here it was, right in front of us. And it was truly special.

Antigua BABY!

It took us another 4-6 hours from there. We had to come across the channel, into the dock. But if it had taken 40-60 hours I wouldn’t have cared. We had made it. It was over.

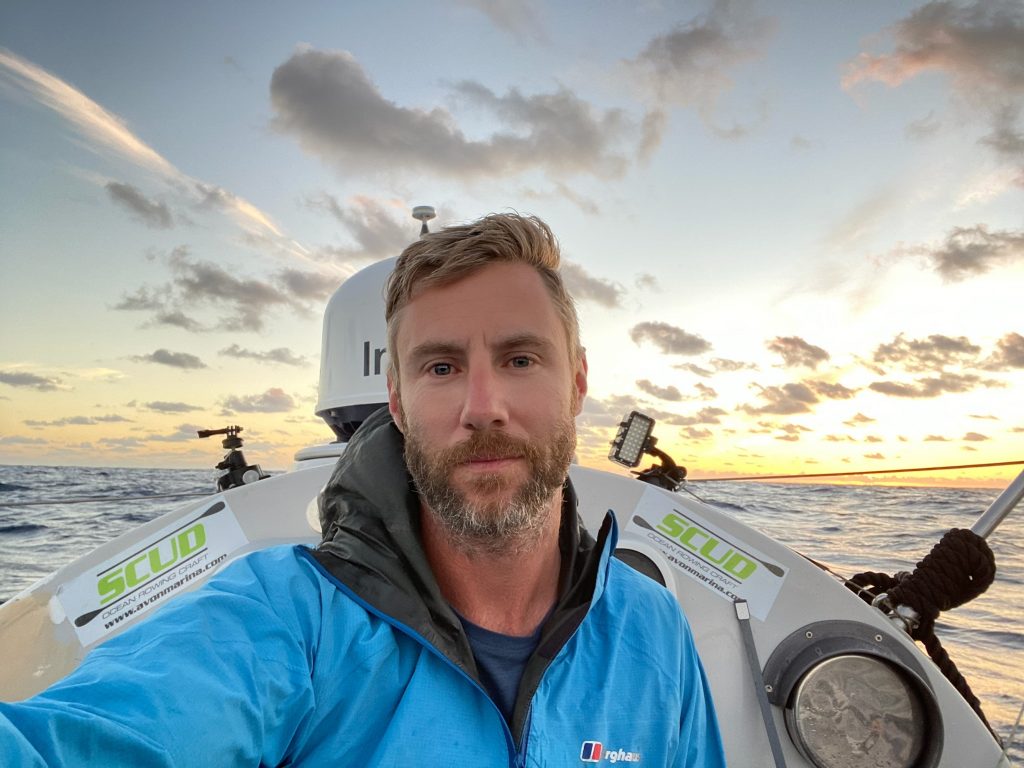

I hadn’t showered or shaved in 2 months. Hadn’t stood up, or taken a step in 2 months. Hadn’t checked email, watched a movie, or eaten fresh fruit or veg in two months. All of that was about to change very soon.

We approached English Harbour instead of the pre-arranged Jolly Harbour. Due to all the COVID nonsense, Jolly Harbour was closed. English Harbour was nearer anyway so made much more sense. We pulled in, stepped foot on the deck to a small smattering of people and media. We had done it. Finally. A wave of relief, and a wobbly stance, rinsed over me as I stepped onto the jetty.

I was handed a glass of champagne, drunk it in approximately 30 seconds, was instantly handed another. But my sea legs got the better of me as I was stumbling around, and I dropped it and smashed it on the floor! Cringe.

The next hour was all a bit of a whirlwind. Alex, the owner of 2 of the most popular spots on the island, had kindly welcomed us to Catherine’s beach bar. Free flow booze, media interviews, and a weird release of stress and anxiety. I plonked myself in a kind of bean bag chair. Beer in one hand, champagne in the other. I sat in silence, watching the noise and chaos unravel around me. It was a little overwhelming, truth be told. I hadn’t seen, nor spoken, to anyone but the boys for 2 months. Suddenly there was a huge buzz. It felt quite odd. Not bad, but out of sync with my last 8 weeks.

People were asking me questions, getting photos. All I wanted was to sit in that bean bag and soak it up. I can barely even remember my first real food. I remember ordering an orange juice and loving it. And I think I ate a hummus and cheese wrap, but I couldn’t be sure. I was just so, so relieved to be off that bloody boat.

The Aftermath of the Row

That evening, we were Alex’s guests at Antigua’s best restaurant, Sheer Rocks. And we celebrated in style (THANK YOU ALEX!!). Cocktails, magnum’s of wine, delicious food, and an after-party until 5am. We still hadn’t slept, but I guess we were used to being sleep-deprived. What a night.

The next day, I woke up a little groggy, grabbed my laptop, and went to a posh hotel. There, I ordered a proper coffee, the first for months, and sat and went through my work emails. It was heaven. I love my work. My blog, my SEO stuff, our non-profit, the wild trips to obscure destinations. And to be away from it all, from my emails, my business, it was weird. I spent the whole day there. About 8 hours, racking up over $100 in coffee and food. The best $100 I have spent in a long, long time.

We stayed in Antigua for 4 nights if I remember rightly. I wasn’t too surprised after all that had preceded it, but the company had organise a pretty awful guest house to be brutally upfront about it. No air-conditioner in the heat of a Caribbean summer, no functional internet, full of mosquitoes, no breakfast or food facilities, and no hot water (after 2 months without a shower, that was a heartbreaker!). I had been dreaming of all those things for months, longing for a nice bed and a comfortable shower and hotel so to discover we had none of them was tough on the mind! But whatever, the ordeal was over and before long I’d be back with my family in England.

So Antigua was beautiful, Alex and the Sheer Rocks team were amazing, but with the state of our accommodation, I couldn’t get back to England quick enough. British Airways surprised us all with upgrades to business class and a bottle of champagne each on the flight to London, and with that, I was back with my loved ones.

Final Thoughts on Rowing the Atlantic?

At the crux of it, I’m just happy it’s over. And I think I’m glad I did it, although I’m not sure. The whole experience brings back some pretty tough emotions deep inside me. And 2 months later, I still can’t grip anything due to the lingering pain in my fingers from ‘rowers claw’.

No doubt, Brexit & COVID stole a few weeks of my life by delaying the thing. The chaotic nature of how the whole operation was organised cost more time. The life-raft issue, the ill-fitting oars, the lack of safety drills or sea trials – all that stuff, whilst pretty unprofessional, and cost me yet more weeks of my life, but I’m still alive to tell the tale. So all’s well that ends well I guess. None of that chaos, ultimately, was why I had the experience I did. The truth is that I was faced with self-reflection in a way I never envisaged, and it was a struggle. But one I’m probably stronger for. Time will tell.

The main question that remains though, was it worth it? You’ll be happy to hear that yes, it was all worth it. Just about. Not because it was a physical accomplishment. But for me, I faced some demons I never had the courage to confront before. The internal lessons learned, the epiphanies I had. The self-awareness gained. But it came at a heavy price.

There is one lingering worry though. The BBC picked up my story, everyone wanted a podcast or interview with me. Amazing, they screamed. And still, I felt like it was undeserved. Sure, I suffered in that boat, but noy how they think. Not physically.

I know that rowing an ocean sounds epic, the kind of thing only legends can dream of. You think of titans rowing hard, breathing deep, pushing with every sinew. You marvel at old guys doing it at 75, or young girls solo at 21. How is it possible you wonder? But it’s just not true. Anyone with more money than sense can do it. Nature does most of the work, so I have been left thinking what are people giving me the adulation for? Why are they revering my ‘achievement’? Because I suffered on a small boat for 2 months? What choice did I have? I couldn’t get off. And I promised myself, in those dark days on the boat, that I’d write an honest blog post about it all so other people can be more informed about the experience that I was.

I have since read of a few other people’s accounts of ocean rowing. Ben Fogle, for one, would agree with my recollection. He too bravely announced it was not to be recommended. Worst experience of his life. Etc. etc. But that all being said, I’m grateful for the opportunity, and for the chance to reflect deeply on life, and my life in particular. A rare opportunity indeed. Maybe in a few more months, I’ll look back at this blog post with a little more positivity.

But now, the wounds are still fresh, and I don’t want to tell a lie. And induce more congratulations. Tell everyone that ocean rowers are beasts, and therefore I am too, and that it’s a killer physical challenge but I loved every minute. None of that is true. The opposite of all that is true. But one thing I learned during this ordeal, that the truth is the best policy.

What now?

No impending plans for another ocean row! Having said that, rowing across the Irish sea, or the Gulf of Thailand, something short that takes 2-10 days, that would actually be fun. But 2 months again? No thanks! For me, I’m now back in Thailand. My adopted home. I’m back here to check-up on my house build in Chiang Mai.

My next international trip is the Serengeti Marathon in Tanzania. I have organised a charity event to raise money for Cure Parkinson’s with my mum. That should be fun. And then we have a school build for the Burmese refugee community with our non-profit in January in the north of Thailand. Before then, I have a wedding ceremony where I’ll be the GROOM (!) sometime I think in December, and my house should be finished in February. Then perhaps my honeymoon. All-in-all, quite a busy 6 months ahead.

FAQs about Rowing the Atlantic

Why Did You Row Across the Atlantic?

Good question. A few reasons.

1) LAW OF ATTRACTION.

The universe pointed me this way, or at least I pointed me this way. The law of attraction kicked in. I thought I wanted it, and I made it happen. When the opportunity finally presented itself to me, I couldn’t pass it up.

2) CHARITY.

In a time where mental health seems to be causing more problems than ever, this expedition raised about $20,000USD for Humen and Dean Farm Trust.

HUMEN: A mental health charity, with a movement to improve and maintain men’s mental health through campaigning.

DEAN FARM TRUST: An animal sanctuary will also be one of our adopted charities, promoting cruelty-free choices.

DONATE HERE:

Men’s Mental Health with HuMEN:

https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/atlantic-dash-humen

Dean Farm Trust Animal Sanctuary:

https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/atlantic-dash-dean-farm-trust

3) 100% MEAT-FREE EXPEDITION:

I have been plant-powered for almost 4 years now. And to have the boat commit to being 100% meat-free, and plant-powered is beautiful. You don’t need meat to be a beast!

4) OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME.

The logistics, the funding, the PR, the expertise. I have zero ability for all of that. I’m humbled and, even after a pretty horrific experience, still hugely grateful, to have been given the chance. It would have been criminal to waste such an amazing opportunity.

It was a physical, and mental challenge, unlike anything I’ve ever done. Disconnecting from the internet 99% of the days, reconnecting with new people in my team, and of course nature. Facing my fears of claustrophobia and the wide-open spaces. It was certainly an experience.

Who Did You Rowing the Atlantic With?

There were 4 people in the boat with me. Amazingly, we got on really, really well. Next to no friction or arguments at all. These guys had nothing to do with why I found the whole thing pretty awful, in fact, they made it a lot better. I can’t even imagine how I would have found it if I was on the boat with d*ckheads!

Billy Taylor: The skipper, and the boss. A veteran of crossing oceans, and a campaigner for Parkinson’s. He’s, amazingly, rowed the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans. Billy was great. He led from the front, fixed the endless problems on the boat, was always the first to jump into any sh*tty jobs, and he was also a super-strong rower. Sure, MonkeyFist as a company were a little loose in organisation, but Billy as a man, skipper and friend? Top guy.

Matthew Pritchard: Brits may remember him as one of the crew from Dirty Sanchez, or on BBC as ‘The Dirty Vegan’. What can I say? A lovely, lovely, kind, caring thoughtful guy. I had never seen Dirty Sanchez before, but a few of my friends had, and they expected him to be pretty crazy. For sure he’s a fun guy, but not over the top in the slightest. Just a great human to be honest. Humble, sweet, and now a great friend. He’s someone you can really trust.

Martin Heseltine: Martin has spent his life on the ocean, and has more experience with all things water-based than I do with pretty much anything. Martin was my saviour. As simple as that. I owe him gratitude, thanks, apologies and a whole lot more. Without him, I could have been overboard! Gentle, but experienced. Wise and kind. Thank you for everything Martin.

And me. God knows what I offered. At least I kept the true darkness of how I felt pretty much to myself until near the end. I didn’t want to burden anyone but myself with that energy.

How Long Did Rowing the Atlantic Take?

Good question. The world record is 30 days-ish. We certainly didn’t break that. For us, we were into our 8th week when we reached the Caribbean, 52 painful days I think it was. Felt more like 520!

Where Did You Start and Finish?

We started in Lanzarote (Spanish island off the coast of Morocco), but then broke down, got rescued and ended up RE-setting off from Fuerteventura to Antigua (a tiny country in the Caribbean). The first boat to ever do that apparently. Pretty cool!

How Far Was it?!

3200 miles/5150km

How Much Does it Cost to Row Across the Atlantic?

A lot. Which is why I was so grateful to be able to join.

Numbers? Probably somewhere around $100k USD per boat. Add another $20k or so to that for the internet-tech stuff on board that we’re borrowing. Thankfully MonkeyFist had organised most of that stuff, so Martin and I had to cover the last $20kUSD.

But You Can’t Really Swim, Can you!?

I mean, I can swim from a side of a pool to a swim-up bar. Can I swim 10 lengths? No Probably not.

And What About the Boat?

29 foot long, 6 feet wide. You row for 2 hours. Rest/sleep for 2 hours. In those 4 hour blocks. 24 hours per day. For 7 weeks. Where did we sleep? In a tiny space about the size of a queen-size bed. 2 of us at time. And the toilet? Look away guys. Bucket. Back in the ocean. Job done.

Would you recommend other people to Row an ocean?

In short, 99% no. The world is a big beautiful place. Full of challenges, expeditions, beautiful spots. To row an ocean costs somewhere between $10k to $100k, or a year+ of your life chasing sponsorship for it. In my opinion, there are so, so many better ways to spend that kind of time and money. Come build a school with my non-profit. Go and climb Elbrus Europe’s highest mountain then tack the Trans-Siberian, then fly to Tanzania and climb Africa’s Highest Mountain and go on safari. Epic trips. And a million times more fun than ocean rowing.

If you want to physically challenge yourself, this isn’t it. Run the Marathon Des Sables, climb mount Everest in 2023 (with me!), or even all the 7 summits, train and run a 200km ultra, cycle across a country, these are true physical challenges that require physical dedication, training, sacrifice. Rowing oceans you just sort out the finances, and then get on the boat. The achievement is the fact that you come out the other side in one piece after the mental anguish of being cooped up. But the ocean and winds do most of the work. Climbing big mountains, running/cycling/swimming big distances? That’s on you.

If you do want to do it, do it solo or in a 2. It’s much easier. You probably think, as I used to, that doing it in a larger group of 4 for example is easier? Nope, wrong. Solo or in a pair is easier. So much more space and comfort. A cabin to decompress alone when you’re struggling. So for sure, if you have a kind of calling to do it, the way I felt I had, then of course go and do it. If it means something to you.